Mastery, by George Leonard

Notes and highlights from the book which inspired the Ordinary Mastery project

George Leonard’s 1992 book, Mastery, was a key inspiration for starting this Ordinary Mastery project. It’s a small book which began life as an article in Esquire magazine. It’s easy to read and is informed by Leonard’s life experiences and observations, particularly as an Aikido practitioner and teacher.

It is primarily a book about long-term learning and growth through dedicated practice, avoiding the desire for quick results and instant gratification. Throughout the book, Leonard discusses patterns he has observed in society and in people’s attitudes which can help or hinder their progress on their mastery journeys.

What follows is meant more as a reference than an article. The notes are my personal highlights of the nuggets of insight from George Leonard’s work. These insights are woven more naturally into the Ordinary Masterclasses from the perspectives of the ASPIRE Mastery Framework. Participants in the Masterclasses are advised to read the Mastery book before the course, but the notes below should provide sufficient grounding if you don’t have a copy of the book.

Thanks to those signed up to the first Ordinary Masterclasses. I had intended to send out dates and details at the beginning of January but time has flown by. Details to follow in the next day or so…

Part 1: The Master’s Journey

1. What is Mastery

Mastery is more of a process, or journey, than a goal or destination.

Mastery is available to everyone, not just the exceptionally talented.

There are few maps to guide the mastery journey, especially in the modern world which could be viewed as a prodigious conspiracy against mastery, where promises of instant gratification and quick fixes lead us astray.

The mastery journey begins with a decision to learn a skill, and it’s good to start with a clean slate without having to unlearn bad habits.

It begins with baby steps, but we feel clumsy and disjointed, having to think about every move, and thinking gets in the way of graceful spontaneous abilities.

We have breakthroughs where we can perform without having to think so much, but our desire for results is unfulfilled when we find ourselves on the plateau, as days or weeks pass without apparent progress.

In our modern anti-mastery society, being on the plateau can feel like purgatory for most people, especially if we are excessively goal-orientated.

Our frustration on the plateau may reveal our true motivations - that we didn’t pursue mastery for its own sake, but for the sake of looking good, or being better than our friends, or for quick wins.

The process of improvement is incremental, you can’t skip stages.

Every time we progress to the next stage we encounter setbacks, where we have to consciously think about what we are doing. Which causes things to temporarily fall apart.

With every setback we face choices - do we quit, do we double down on our efforts, do we take it less seriously and just have fun, or do we choose the process that leads to mastery?

Quick-fix choices bring only the illusion of accomplishment, the shadow of satisfaction.

Our choices affect the realisation of our potential.

We are each born with varying intelligences as described by Howard Gardener: Linguistic; Musical; Logical/mathematical; Spatial; Bodily/kinesthetic; Intrapersonal; and Extrapersonal.

We are geniuses in potentia, distinct from animals through our physical and cognitive adaptability.

When pursuing mastery, we learn as much about ourselves as the skill we are learning.

Progression along any mastery journey is always the same, with occasional spurts of improvement with much of our time spent on the plateau when improvement seems elusive.

Neuroscientist Karl Pribram identified hypothetical brain-body systems, one of which is the ‘habitual behaviour system’. Our cognitive system and effort system are involved in deliberate learning. Spurts occur after the conscious work of the cognitive and effort systems have been incorporated into the unconscious habitual system.

We move forward with mastery by practising for the sake of practice itself.

2. Meet the Dabbler, the Obsessive, and the Hacker

We may see ourselves in the three archetypal characteristics which prevent us from taking the path of mastery.

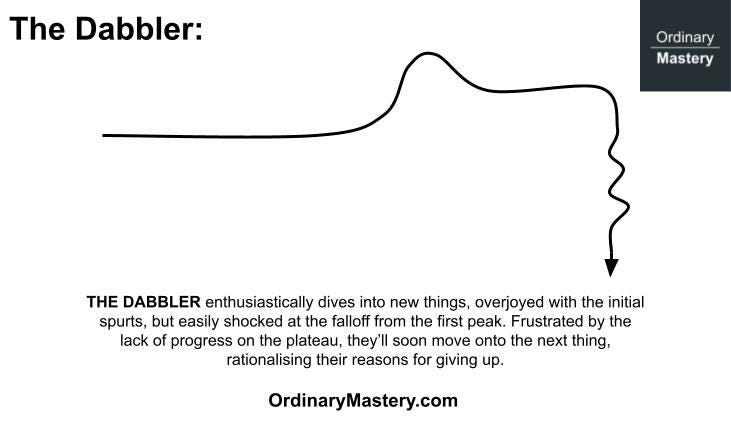

The Dabbler enthusiastically dives into new things, overjoyed with the initial spurts, but is easily shocked by the falloff from the first peak. Frustrated by the lack of progress on the plateau, they’ll soon move on to the next thing, rationalising their reasons for giving up.

In relationships, the dabbler specialises in honeymoons, enjoying the seduction and surrender with their ego on parade, but soon moves on to the next love interest.

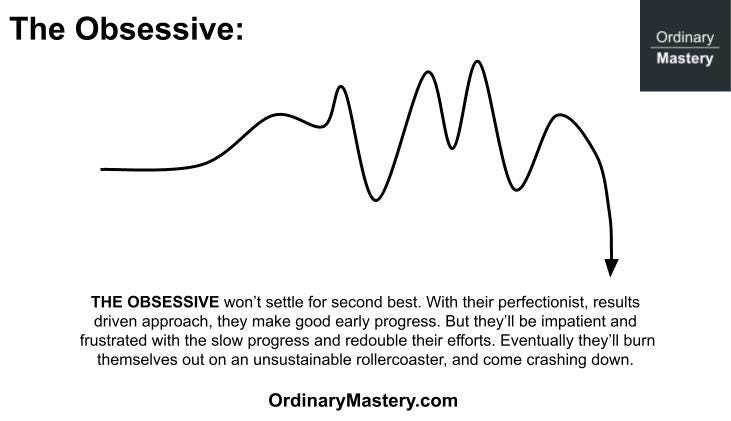

The Obsessive won’t settle for second best. With their perfectionist, results-driven approach they make good early progress. But they’ll be impatient and frustrated with the slow progress and redouble their efforts. Eventually, they’ll burn themselves out on an unsustainable rollercoaster, and come crashing down.

In relationships, the obsessive sticks around after the honeymoon period but goes over the top with a stream of romantic gestures to recapture the initial excitement but this can quickly descend into stormy relationships where both people get hurt. The obsessive doesn’t learn that relationships require slow nurturing and self-development.

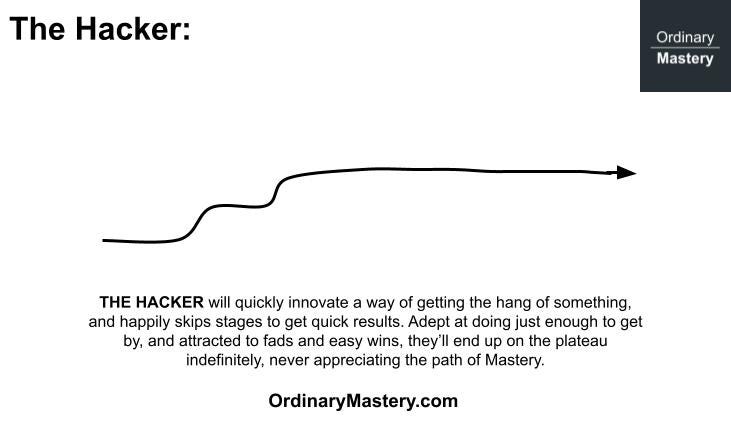

The Hacker will quickly innovate a way of getting the hang of something and will happily skip stages to get quick results. Adept at doing just enough to get by, and attracted to fads and easy wins, they’ll end up on the plateau indefinitely, never appreciating the path of mastery.

In relationships, the hacker is seeking comfortable refuge from the uncertainties of the outside world, rather than for learning and self-development. The relationship breaks down if their partner moves forward in their development while the hacker is content staying on the plateau.

In lectures and workshops, Leonard polls the audience to ask which archetype best describes their character, and the response tends to break down into nearly even thirds.

3. America’s War Against Mastery

The cultural references in this chapter may seem outdated but the principles still apply in America and Westernised cultures in general.

Embarking on a mastery journey means bucking the consumerist trends of modern society which represent a War on Mastery.

Our traditional value systems have been replaced by consumerism and unprecedented choices about which non-necessity we spend our money on.

Modern values are influenced by advertising, a campaign against long-term effort, which appeals to the hedonistic, envious, or fear-driven aspects of ourselves.

Modern society emphasises the climactic moment over the plateau, leading us to expect a life of continual climaxes and we become frustrated with the realities of life.

The desire for the climactic moment, the path of endless climax, instant fame, overnight success, or temporary relief, is destructive to the rhythm of mastery.

The anti-mastery attitude is also prevalent in businesses driven by impatient shareholders prioritising near-term profits at the expense of balance and growth.

The same is true of governments seeking short-term solutions to complex issues with a ‘growth at all costs’ mentality.

The result is shoddy products, epidemics of obesity, drug addiction and gambling.

In the long run, the war against mastery - the path of patience, and dedicated effort without attachment to immediate results - is a war that can’t be won.

4. Loving the Plateau

Early in life, we are taught that we should put effort into something in order to get something else - study hard so we get good grades, get good grades so we can go to college, and graduate from college so we get a good job.

While goals are important, the real rewards in life can be found in the process, of how it feels to be alive, but we are never taught how to enjoy the plateau - so many of us indulge in self-destructive behaviours to escape it.

On the plateau, we can learn to enjoy regular hard practice for its own sake, with no particular goal in mind, without the worm of ambition eating away at us.

We need to stay on the plateau as long as is necessary to avoid the perils of getting ahead of ourselves.

Every human activity which involves significant learning - physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual - is paradoxically exceptionally demanding, unforgiving, yet rewarding.

Despite the War on Mastery, there are millions of people who are dedicated to the process as well as to the product - people who love the plateau - fed by the ordinary routine itself.

Goals and contingencies are important, but they exist in our minds in the past and the future. Practice, on the path of mastery, exists only in the present.

To love the plateau is to love the eternal now.

Part 2: The Five Master Keys

Human beings learn prodigiously from birth to death.

This is what sets us apart from all other known life forms.

Man is a learning animal.

In this light, the mastery of skills that are not genetically programmed is the most characteristically human of all activities.

The world is our school.

We all participate in a mastery journey in early childhood when we learn to talk and walk. Every adult or older child around us is our teacher.

But when we are older and face learning skills in the absence of a cooperative and supportive environment we must find our own doors to mastery.

The following are the 5 keys for opening the doors to mastery.

5. Key One: Instruction

Finding first-rate instruction is the best thing you can do, even though there are some benefits of being self-taught (not knowing what can’t be done and therefore breaking new ground) the self-taught person is on a chancy path.

Even those who will someday overthrow conventional ways of thinking or doing need to know what it is they are overthrowing.

Teachers come in many forms - in person, in books, groups, classrooms, friends (and now YouTube or Substack!)

Experts can be lousy teachers

Instruction demands humility, a good teacher delights in being surpassed by their students.

Judge a teacher by their relationship with their students.

Scorn, exhortation, humiliation, anything that destroys the student’s self-confidence and self-esteem, is ineffective. A good teacher shows respect for the student.

Knowledge, expertise, technical skill, and credentials are important, but not as important as the empathy and patience needed when working with beginners.

Our enthusiasm for excellence and high performance as teachers may inadvertently impair our effectiveness when teaching the less talented.

The most talented students don’t always turn out to be the best, those who make good early progress often have trouble staying on the path of mastery.

Hard work and experience beat talent.

When you learn too easily, you’re tempted not to work hard, not to penetrate to the marrow of practice. The worst horse that is whipped to the marrow of its bones can become the best horse (See Shunryu Suzuki’s Four Horses example).

The exceptionally talented person will have to work just as hard, if not harder, than the person with mediocre talents to fulfil their potential.

Make sure your instructor is paying attention to the slowest student on the mat.

The best teacher is not the one who gives the most polished lectures, but the one who knows how to involve each student actively in the process of learning.

Just like students, teachers can also be obsessively goal-oriented, indifferent, lazy and inept.

The student should maintain the right psychological distance from the teacher. Too far removed and the student will not surrender to the practice, too close and they risk becoming a disciple rather than a student.

On the path of mastery, learning is never-ending.

6. Key Two: Practice

We often see practice as a verb, e.g. to practice the trumpet, but for someone on the master’s journey, practice is a noun - not something you do, but something you have, or something you are.

The Chinese word ‘tao’ and the Japanese ‘do’ literally translate as the road, the path, or the way. Practice is the path upon which you travel.

In mastery, practice is part of life, not as a means to get something, but for its own sake.

The master, and the master’s path, are one.

The rewards are great, but they are not the reason for the journey.

The traveller is fortunate when for every mile they travel, the destination is two miles further away - that’s a sign of a profound and meaningful mastery journey.

Devotion to the goalless journey is an infinite game where the point isn’t to win, but to keep playing. The quality and excitement of the game are more important than which team wins.

The love of practice isn’t about practising to get better, but if you do love your practice, getting better happens naturally.

Staying on the mat - the master stays training on the mat longer than others.

The master of any game is generally a master of practice.

To practice regularly, even when no progress is being made, seems onerous. But eventually, the day comes when your practice becomes a treasured part of your life.

Practice is the path of mastery.

When life presents its ups and downs, your practice becomes the most reliable thing in your life.

Practice might eventually make you ‘successful’ or a ‘master’ in your field, but that isn’t the point. Mastery is the practice, mastery is staying on the path.

7: Key Three: Surrender

The courage of the master is measured by his or her willingness to surrender.

Firstly, we must surrender ourselves to the wisdom of our teacher.

Secondly, when learning anything, we must surrender ourselves to the indignities of failure.

Thirdly, we must surrender ourselves to countless repetitions of practice.

At first, this sounds boring, but the essence of boredom is the obsessive search for novelty. Satisfaction lies in mindful repetition, the discovery of endless richness in subtle variations on familiar themes.

The stories of the East are rich with indignities on the path to mastery - ‘chop wood and carry water’, as the saying goes.

To improve at something, we have to make changes which in the short run will make us worse, everything falls apart, but we must surrender to the process, we must renounce a present competency for a higher or different one. We must surrender, and let go of our expertise.

For the master, surrender means there are no experts. There are only students.

8: Key Four: Intentionality

Intentionality is a combination of character, willpower, attitude, visualisation - the mental game.

Many sports stars relate their success on the field to the vividness of their mental practice.

Arnold Swartzenneger claimed that one rep with full mindfulness was worth ten without.

Experiments, and George Leonard’s anecdotal experiences, have proven the effectiveness of vivid imaging, or visualisation, as part of one’s training practice.

Is consciousness a mere epiphenomenon, as behaviourist B.F. Skinner would claim? Or is the poet William Blake right in suggesting that mental things alone are real?

“More and more, the universe looks like a great thought rather than a great machine” according to astronomer Sir James Jeans.

Leonard appears to be raising the question of whether our thoughts and the material world, are interdependent and related so that one may influence the other.

A transformation from the imagined to the real is what the process of mastery is all about, hence the importance of intentionality.

Intentionality fuels the master’s journey. Every master is a master of vision.

9. Key Five: The Edge

While masters are zealots of practice and connoisseurs of the small, incremental step, they are paradoxically likely to take risks in challenging themselves to surpass previous limits, and even at times prone to becoming a little obsessive at that pursuit.

They will explore the edges of their capabilities.

They will walk the fine line between endless goalless practice, and pursuing the alluring goals that emerge along the path.

They will periodically put themselves through intense ordeals, trials by fire, tested physically and psychologically to their limits.

Their success in these moments is not an expression of ego, but an expression of essence. A moment of climactic transcendence during a long journey.

But it is the journey that counts: Before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood and carry water.

One must submit to years of instruction, practice, surrender, and intentionality before playing the edge.

After playing the edge, it’s back to training, practice, and much time on the plateau on the never-ending path of mastery.

Part 3: Tools for Mastery

10. Why Resolutions Fail, and What to Do About It

Backsliding is a universal experience.

We all resist change, our body is wired to maintain equilibrium and homeostasis.

We are a self-regulating system of feedback loops and continual adjustments to maintain homeostasis.

Homoeostasis is both a physical and a psychological phenomenon.

We also see homeostasis in social groups that require stability and security, our societies are held in place by legal and cultural feedback loops and controls. Social norms prevail.

Homeostasis can’t distinguish between good change and bad change, it resists all change. If we are accustomed to a sedentary lifestyle, exercising suddenly is seen as a threat, causing us to panic when our heart rate rises.

If your family system is used to drama and dysfunction then stability won’t last long, soon, something will happen to disrupt the peace again.

Trivial changes or bureaucratic meddling are easier to accept than big changes (whether favourable or unfavourable)

Individuals, families, and groups do change, however, and homeostasis is reset at a different equilibrium.

But to change we always have to deal with homeostasis in the form of resistance from friends, family, and co-workers - or even ourselves in the form of self-sabotage.

At the point of turning pro in your career perhaps, after years of hacking away at it, and instead approaching it with an attitude of mastery, you will meet with homeostatic resistance from your co-workers and your self-identity.

Even applying the principles of mastery to hobbies like gardening or tennis will meet with resistance because the required changes ripple out to many areas of our lives.

So often, the gravitational power of homeostasis lures us into backsliding into the old habits of the Dabbler, the Hacker, or the Obsessive.

There are Five Guidelines for resisting homeostasis and staying on the path of mastery:

Be aware of how homeostasis works:

Expect resistance and backlash - it’s a sign you’re making important changes rather than a threat.

Don’t panic at the first sign of trouble.

Remember that an entire system has to change when any component part changes.

If people are undermining your efforts they may not wish you harm, it’s just how homeostasis works.

Be willing to negotiate with your resistance to change:

When the alarm bells of resistance ring, don’t back off, but don’t blindly push through either.

See pain not as an adversary, but as the best possible guide to performance.

Keep pushing, but with awareness.

Don’t just push through resistance without awareness because that puts the whole system at risk.

Be prepared for serious negotiation.

Develop a support system:

The best support system involves people who are going through the same change as us or who have been through it before.

Leonard provides the example of Johan Huizinga’s book, Homo Ludens and how sports and play bring people together. Brian Eno’s concept of a Scenius (Scene and Genius) also plays into this.

A support group is a mutual withdrawal from the world and rejection of the usual norms.

If there are no fellow voyagers on the same journey, then ensure you ask for support from your friends and family.

Follow a regular practice:

Practice is the foundation of the path of mastery.

Practice is a habit, so any regular practice provides an underlying homeostasis as a stable basis during periods of change.

Dedicate yourself to lifelong learning:

To learn is to change.

The lifelong learner is someone who has learned to deal with homeostasis because they are doing it all the time.

Leaning is the mastery path that never ends.

11. Getting Energy for Mastery

Remember the adage ‘If you want something done, get a busy person to do it’ when we don’t feel we have the time needed for mastery.

We can probably all remember times when we had a rush of energy to face a challenge and no mountain seemed too high.

Human beings are like a machine that wears out through lack of use.

Paradoxically, we gain energy by using energy - think about how energised we can feel after exercise.

Look at the energy of a child, full of raw unadulterated learning, playfully exploring their environments - but there’s a tendency for adults to restrain a child’s energy - ‘sit down and be quiet’ - and natural curiosity is dulled by the bureaucracy of conventional schooling which encourages passivity.

Society quashes the playful exuberance of energised individuals.

Einstein: “It is nothing short of a miracle that modern methods of instruction have not yet strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry.”

High energy is a threat to conformity.

Leonard gives Seven guidelines for gaining energy:

Maintain physical fitness

People who feel good about themselves are in touch with nature and their bodies and are more likely to use their energies for the good of the planet.

Acknowledge the negative and accentuate the positive

Optimistic people tend to have more energy

But don’t deny the negative (toxic positivity), as there are situations in life that need correcting. Denial inhibits energy.

Face the truth, and move on.

Try telling the truth

Truth-telling works best when it involves revealing your feelings, rather than as a tool to insult others or get your way.

Truth-telling is an energy release, it involves risk, excitement, and challenge.

Honour, but don’t indulge your dark side

We have a lot of energy stored up in what Carl Jung termed our shadow

The shadow is the repressed and submerged part of our personality, things about us we have unconsciously denied and hidden to gain self-acceptance and acceptance of society.

But those hidden parts of ourselves can be expressed through our creativity or artistic expression, creating a great deal of energy in the process.

When we feel the energy of our dark side, we don’t need to express it in our behaviour or knee-jerk reactions to situations, we can use it to inspire us to work furiously on a project.

We can transmute the energy beneath our anger into fuel that we can use on our journey of mastery.

Set your priorities

To move in one direction you must forego all others

If you keep all your options open, you can’t do a damned thing

The endless possibilities and choices of modern life lead to paralysing indecision. We become comatose, depleted of energy.

The liberation of energy comes through accepting limits.

Make commitments and take action

The journey of mastery is ultimately goalless, but there are interim goals along the way.

A tough short-term goal with a firm deadline is immediately energising

We get an immediate surge of clarity and energy when making a firm commitment

When externally imposed goals aren’t available, we can set our own, and making it public means we will take it more seriously.

Get on the path of mastery and stay on it

Regular practice not only elicits energy but tames it.

Without the discipline of underlying practice, deadlines can produce violent swings between frantic activity and collapse.

The master’s journey brings perspective, helping us keep a flow of energy between the low moments and the highs.

We can’t hoard energy, we can’t build it up by not using it.

12. Pitfalls Along The Path

It’s easy to get on the path of mastery, the challenge is staying the course.

George Leonard discusses thirteen potential pitfalls:

Conflicting way of life

The path of mastery does not exist in a vacuum but wends its way through ordinary obligations, pleasures, and relationships.

If our mastery path is not aligned with our career or livelihood we must create the space for it.

But the average person wastes an awful lot of time watching TV (or scrolling social media), so it is generally possible to make time.

“Never marry a person who is not a friend of your excitement,” says psychologist Nathaniel Brandon

Ultimately we should strive to live our ordinary lives according to the mastery principles.

Obsessive goal orientation

It’s fine to have high aspirations but the best way of reaching them is to have modest expectations at every step along the way.

Don’t keep looking at the mountain peak ahead, keep your eyes on the path.

When you reach the top of the mountain, keep climbing.

Poor instruction

Surrender to your teacher only as a teacher, not as a guru.

But the ultimate responsibility of getting better lies not with your teacher, but with you.

Lack of competitiveness

Spice analogy: Competition provides spice in life and sports, only if the spice becomes the whole diet is it a problem.

You must play to win when in a competition, it’s an opportunity to hone your skills at the edge.

Winning graciously, and losing with equal grace are the marks of a master.

Overcompetitiveness

If winning is the only thing, it relegates practice, discipline, conditioning, and character to nothing.

Overcompetitiveness creates more losers than winners, especially when overcompetitiveness features at the very early stages of our lives when we can’t handle the crushing blows.

Laziness

Courage is the best possible cure for laziness.

Injuries

People often get hurt through obsessive goal orientation.

Surpassing previous limits involves negotiation with your body rather than ignoring its warnings, negotiation involves awareness.

Avoiding serious injury is more about being conscious than being cautious, and this is probably true of emotional injuries as much as physical ones.

Drugs

Drugs appeal to those seeking quick wins and climactic moments without spending time on the plateau.

If you’re on drugs, you’re not on the path.

Prizes and medals

When overused, extrinsic motivators can prevent progress on the mastery journey.

This is probably due to the expectation effect and the ensuing blows when expectations are not met.

We won’t see the limits of human potential until we realise the ultimate reward is not a gold medal but the path itself.

Vanity

If you got on the path of mastery to look good you must realise that first, you need to be willing to look foolish.

If you’re constantly concerned with appearances you will lack the concentration needed for effective learning and top performance.

Dead seriousness

Without laughter, the rough and rocky parts of the path would be too much to bear.

Hunour brings out more perspectives and combats the tunnel vision of dead seriousness.

Beware of grim or self-important travelling companions.

Inconsistency

Consistency, time and place establish the rhythm of mastery.

Consistent rituals around our practices buy us more time for practice and means we don’t have to think about it so much.

But if we miss a few sessions, there is no reason to quit.

“Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds”, Raph Waldo Emmerson

Perfectionism

Great works of art and achievements are easily accessible to us, but ‘comparison is the thief of joy’ - be inspired rather than envious or disheartened.

Mastery is not about perfection, it is about process.

The master is the one who stays on the path day after day, year after year.

13. Mastering the Commonplace

Our preoccupation with goals, results, and quick fixes has separated us from our own experiences.

The quality of a Zen student’s practice is defined just as much by how he or she sweeps the courtyard as by how he or she sits in meditation.

George Leonard then goes on to describe how applying the principles and conscious mindfulness of mastery to ordinary chores gives us back the time that those chores would have consumed and turns ordinary activities into a high art as we pay attention to the rhythm and movement of our bodies in their performance of chores.

Life is full of opportunities to practice the unhurried rhythm of mastery which we are denied in our goal-focused results-driven rhythms.

On the level of personal experience, all of life is seamless and connected, despite efforts to break it down into compartments and categories.

It’s bizarre that we can give full the attention of the master in practising our backhand in tennis, yet be completely disconnected and aloof in our relationships.

Mastery in relationships requires practice, just as in acquiring skills - and there will also be long periods to patiently endure when relationships plateau.

Relationships can also be improved with instruction (e.g. counselling - of the non-vapid kind), practice, surrender, intentionality and playing the edge.

Ultimately nothing in life is commonplace, or ‘ordinary’, nothing is ‘in-between’. The threads that join our every act are infinite, and all paths of mastery eventually merge.

14. Packing for the Journey

In this chapter, Leonard begins by encouraging us to take the first steps on our mastery journey and gives a checklist of items for our backpack, these items are a checklist of the advice in the book so I will not be covering them again here.

Next, he uses the body as a metaphor for further advice and practices focused on balancing and centring the physical body, and relaxed breathing. He sees the physical body as a metaphor for everything else in life, our work, our relationships, our chores - everything can be done from a sense of balance and centring. He also parts by leaving us with the Eastern idea of ki, or chi - an unseen energy force harnessed in Eastern medical practices and martial arts.

Epilogue: The Master and the Fool

Leonard begins by recounting a story of an encounter with a sculptor who had lost his creative spark, declaring that he had stopped being a learner. The sculptor asks for Leonard’s advice on how to become a learner again. Leonard replies, “It’s simple. To be a learner you’ve got to be willing to be a fool.”

The fool is not a stupid or unthinking person, but someone with the spirit of the medieval fool, the court jester. The carefree fool of the number zero tarot card which signifies the fertile void which gives birth to creation - the emptiness from which things come into being.

Leonard refers to a story of a Zen master filling up a cup with water, continuing to pour even after it is full. Signifying that the full cup, like our full minds, has no space for anything new.

The babbling baby is encouraged by his father to babble some more, to make approximations at a word, and to be a fool until finally uttering a word correctly. The baby is not chastised when making mistakes but encouraged.

Leonard asks, how many times have we failed to try something new out of fear of being thought silly? And how often have we censored our spontaneity out of fear of being thought childish?

Abraham Maslow discovered a childlike quality in people with high potential. He calls this a ‘second naivete’.

Ashleigh Montagu used the term neotany (from neonate or newborn) to describe the eccentric genius of Einstein and Mozart - they were free to be foolish.

The deathbed wish of Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, was to be buried in his white belt. The belt of the beginner, despite being the world’s highest-ranking judoist.

At the moment of death, the ultimate transformation, we are all white belts.

If death makes beginners of us, so does life.

Leonard signs off by asking ‘are you ready to wear your white belt?‘

John -- I love this post, not just for its content (which is great) but also because I too was inspired by George Leonard's 1992 article, and then the resulting book. In fact, I have a hilarious story about meeting him at a writer's party a few years after the book came out, going nuts over his book, and then explaining why to all the other writers standing in the kitchen with us. Leonard was not only a great writer but also a great guy, who I sorely miss.

Keep up the good work. And when you have a moment, please check out the podcast I produce in my multimedia magazine (Craftsmanship) called "The Secrets of Mastery."

This is a brilliant post; I can’t even fathom how long it must have taken you to research, write and edit it, but thank you. However, I think you’ve got the concept of homeostasis wrong; this isn’t like a fixed set point, like the water in a bathtub. If you jump into the tub, the water line is disturbed. Biological homeostasis is closer to harmony, in that there are a multitude of variables all interacting at any given time, and the organism requires a certain chord to be played, at a certain cadence, to play just right. Syncopation is desired in that ecosystem, not shunned.