George Leonard’s 1992 book, Mastery, describes four archetypes, or categories of personality traits. The four archetypes relate to different ways of approaching our tasks and interests.

The four archetypes are The Dabbler, The Hacker, The Obsessive, and The Master.

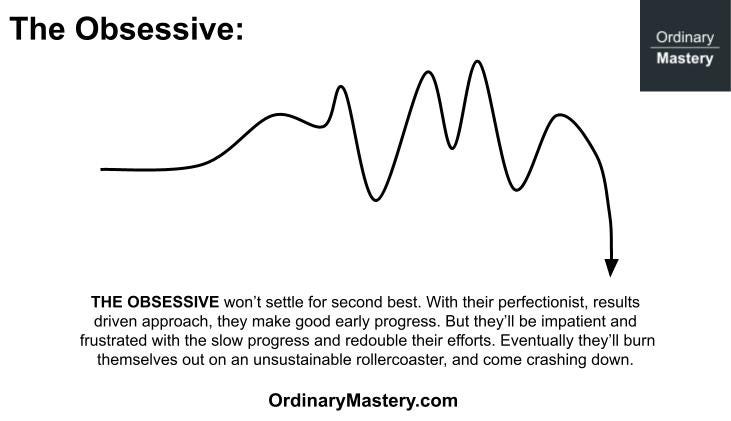

Here we are meeting the obsessive…

George Leonard’s obsessive archetype refers to an individual who has a compulsive drive to achieve mastery in a particular skill or activity. The obsessive is characterised by an intense focus on results and a compulsion to put in long hours of practice but often lacks balance and perspective.

Some key traits of the obsessive archetype include:

A compulsive drive:

The obsessive has a strong compulsive motivation to achieve expertise in a particular skill or activity, often putting in long hours of practice and dedicating the majority of their time to the pursuit.

An intense focus:

The obsessive tends to have an intense laser-like focus on the pursuit of excellence, but they may become too narrowly focused and fail to see the bigger picture.

An intolerance for failure:

With their identity and self-worth tied closely to their success, the obsessive may become discouraged or angry with themselves in the face of failure or when progress plateaus. However, they always feel they are failing because they don’t ever have the results they want.

A lack of balance:

The obsessive may engage in excessive practice, putting in long hours without enough breaks, and are never satisfied with their progress. They become so consumed by their blinkered drive for expetise that they have a lack of balance and perspective in other areas of their life such as tending to their health and relationships. They may experience burnout.

Unable to appreciate the journey:

The relentless drive for results leaves the obsessive with an empty experience of the journey. They are never satisfied with their progress and are unable to appreciate the finer details of their learning experience.

Burning obsession

“Today, everyone is an auto-exploiting labourer in his or her own enterprise. People are now master and slave in one. Even class struggle has transformed into an inner struggle against oneself.” - Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society

We do indeed seem to live in a Burnout Society, as described by contemporary Seoul/Berlin-based philosopher, Byung-Chul Han. We live in what he calls an ‘achievement society', where enough is never enough, characterised by a competitive striving in every activity one pursues. This achievement society has replaced what French Philosopher Michel Foucault called a 'disciplinary society', where people are subverted and controlled by the presence, or tacit threat of, constant surveillance and punishment. Living in Byung-Chul Han’s achievement society, people no longer face a disciplinary world of hospitals, madhouses, prisons, barracks, and factories, but an alternative regime of fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories. As entrepreneurs of ourselves, we are no longer “obedience subjects” but “achievement subjects”.

More from George Leonard on the obsessive

George Leonard talks about how the obsessive wants to do things right the first time, intolerant of failure, they are unacquainted with the beginner’s mind of the master. They have something to prove, they need results. So no expense is spared on books, tools, equipment, resources, apps, training, or whatever it takes to make satisfactory progress.

The obsessive puts in extra hours by default, mercilessly pushing themselves, and self-flagellating for any lack of progress. They are bottom-line, results, and outcome-driven kind of people who will redouble their efforts when hitting a brick wall, eschewing any wise counsel from others advising moderation.

The obsessive doesn’t lack grit but unlike the dabbler doesn’t know when to quit. The obsessive archetype craves progress, only wants results, and cannot appreciate that human development is a process, one that requires the fertile ground of the plateau, when it seems we’re getting nowhere.

In romantic relationships, the obsessive will not be able to stand the decline when the honeymoon period ends, so they will lavish their partner with ever more extravagant gifts and intense gestures - a hot and cold rollercoaster relationship until the inevitable dramatic breakup.

The compulsive goal orientation of the obsessive leaves no room for enjoying the journey, their lives instead will be chaotic and unstable, who super high highs, and depressingly low lows.

The obsessive and our external ecosystem

In our wider environment, we feel the societal work ethic, a hustle culture, that equates success with overworking, where our self-worth is coupled with the grind, where the grind is virtuous and if we’re not yet successful we must grind harder. We mistake an attachment to our work ethic as our main source of fulfilment and future happiness, at the expense of our health, relationships, and sense of meaning.

Burnout is often blamed on the person, but the pathways to ‘success’ are given to us from an early age. Work hard at school, get good grades, conform to the norms, and work hard as an adult to earn your success. Follow the default path that society expects you to follow as author Paul Millerd1 writes about in his book The Pathless Path. We still treat ourselves as units of production, machines from the industrial era where high-performance, productivity, efficiency and results are commonly used terms in modern workplaces to measure your output, and your worth. Anyone who deviates from this default path is a slacker, a rebel, or a dissenter.

Companies and society often exhibit high time preference attitudes, mostly concerned with the needs of the present moment, whereas a low time preference attitude delays present gratification, emphasising future needs. Companies focusing on short-term results, often quarterly-driven results, bother less about the process. They hire goal-oriented results-driven employees, using metrics such as KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) to measure the performance of their resources people.

Obsessive working is further glamourised online by what has been termed hustle culture, people virtue signalling their work ethic to one another where burnout is a badge of honour, and toil glamour is celebrated as a lifestyle. Young Gen Z and Millenial men, keen to assert their status, seem particularly susceptible to the macho ‘rise and grind’ - if you’re not up at the crack of dawn following the latest hustle guru’s morning routine for success, living life to the max, implementing the latest productivity hack, then you’re a lazy ass loser underserving of power and wealth.

If you fall prey to hustle culture you’re surrendering your personal power to external definitions of success. Those who have been lured may well be running away from something, working extra hard to avoid insecurities. Workaholism may be the symptom of some deeper unresolved issues, and unchecked chronic stress can lead to health issues. The Japanese even have the term karōshi or death from overworking as mentioned in my recent Kodawari article.

The obsessive in a work environment may be someone motivated by performative productivity, often having many plates spinning at once, always wanting to be super responsive to questions from others, and unable to set boundaries to throttle the rate of incoming requests. And our society rewards this kind of behaviour, we get recognition and performance bonuses (if we’re lucky). Our performant productivity is driven by fear, fear of not looking busy, fear of not being seen as productive - so we double down on our efforts - welcome to burnout.

My own internal obsessive

While I’ve found the hacker, and the dabbler archetypes quite easy to relate to, the obsessive in me hides well. Perhaps my inner dabbler overpowers any obsessive tendencies, always seeking novelty and flirting with too many things at once.

There have been times in my life when I’ve had to dedicate my time in a structured way to achieve specific results. One occasion in the late 1980s was when failing my A-Level mock exams with an ‘E’ grade, and six months later after a serious talk with myself and intense home study, passing with B grades. Another time was in the early 2000s when starting a bootstrapped business, wow that was intense for a while, but I also stuck to my health and fitness regime and tried not to overdo it.

Having long paid attention to my health, I’m hopefully attuned to any sign of burnout. I am also quite good at setting boundaries and saying ‘no’ to external pressures. To be honest, while I can relate to the dabbler and the hacker archetypes, I don't particularly relate to the obsessive. Or am I just blind to it, as I’m typing these words rather later at night after a long day sat mostly at the computer?

From obsessive to master

The obsessive may be the one archetype which is sometimes difficult to distinguish from mastery because the mastery archetype is also characterised by a consistent work ethic and focus. It seems that the difference is a question of attitude and the sustainability of work. The obsessive needs to temper their relentlessness by finding a sustainable pace, setting boundaries, and slowing down to speed up. Perhaps prioritising a health practice of physical exercise, proper sleep, and clean eating. They also need to learn to enjoy and appreciate the journey and fall in love with the process, which will require a considerable shift in perspective. Perhaps taking time to introspect on what drives their need for success. Mastery is not about an obsessive striving for perfection, it is consistent sustainable practice with the beginner’s mind, tolerant and appreciative of failures along the way.

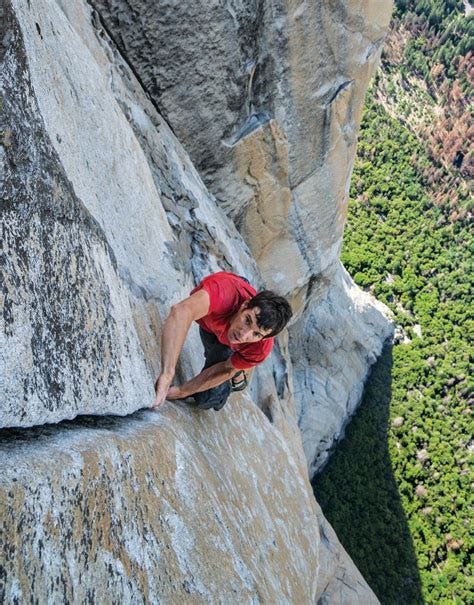

The obsessive is a slave to their ego whereas the master experiences an egoless humbleness. The sports obsessive will push themselves too hard, prone to injury or some other danger. The epitome of mastery is the free climber, someone like Alex Honnold. Honnold reports feeling a sense of egolessness at the rock face, his ego is merged with his surrounding environment. At one with the rock with heightened senses and pattern recognition, from countless hours of ordinary practice, he instinctively knows his next move. He is in flow. The free climber has no need to indulge his ego, for he would risk certain death if he allowed it to push him beyond his physical limitations. The obsessive free climber wouldn’t last long.

The thinking of philosopher Agnes Callard may be helpful here. She distinguishes between ambition and aspiration. Ambition pertains to external measures of achievement such as wealth, power, fame, and status. In contrast, aspiration involves personal development and growth towards our better selves, where accomplishment is defined by our own internal criteria of fulfilment and contentment. For those who are obsessive, it would be beneficial to shift their focus away from external standards of success and discover their inner aspiration. This is explored further in my proposed ASPIRE Mastery Coaching model.

The motivation of a master derives from the work itself, while that of an obsessive stems from the pursuit of the end goal. The master exhibits a lower time preference, characterised by a willingness to postpone immediate gratification, in contrast to the more prevalent high time preference mentality in contemporary society. Shifting one's perspective is challenging, requiring the cultivation of self-awareness, and taking an objective look at oneself. Thus, this article may serve as a helpful impetus for individuals who may not have recognised their obsessive tendencies.

Finally, for the obsessive, it may be worth pondering on the thoughts of the master wordsmith, Kurt Vonnegut:

“I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don't let anybody tell you different.”

Author

blogs at and wrote The Pathless Path illustrating his own story of escaping the corporate default path of success he was expected to follow and instead finding fulfilment in embracing the uncertainty of finding his own path. His book also led me to the thinking of Agnes Callard around Aspiration vs Ambition, mentioned in this article and probably the trigger that led me to conceive what I'm calling the ASPIRE model of mastery coaching.