Mastering the Art of Sucking at Something

Getting used to embracing the suck with the beginner's mind

I hadn’t planned to write this, I should be prioritising another piece that is involving a fair amount of research and thought to complete. But I’ve learnt that when serendipity calls, it always pays to pick up the phone.

I’ve stumbled across a video which has such a deep resonance with the way I am trying to think about mastery and such a simple, believable, and inspiring message, that I couldn’t let it pass without sharing it here.

If you have an aspiration in any field whether in music, writing, sport, work, comedy, acting, cooking, coding or even just being a better person in the art of life, this video by multi-instrumentalist Chris Hayzel carries the message that no matter who you are on the journey of mastery, you will have to endure a tremendous amount of suckiness. Suckiness doesn’t discriminate, but it’s something we can learn to get good at.

Mastery is the art of sucking at something

Chris’ central theme is that it is OK to suck and that getting really good at something will require a high tolerance for being really bad at something for longer than we would like.

He begins by reminding us that when we see the performance of a great artist we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg of their efforts:

“When you go to a show or you're listening to an album or you're watching a performance on YouTube you're really only seeing a small polished finished sliver of that person's creative process…”

“And it's understandable… Who wants to go to a show and watch somebody bumble around aimlessly on guitar?”

- Chris Hayzel

We leave the performance thinking the musician is so talented, but we miss something, and Chris humbly reminds us by reflecting on his own experiences of sucking, saying that “musicians are really well practised at being bad at something, and we continue to be bad at that thing until we’re not bad at it anymore”. Sucking is the reality one must face whilst the mind and body are going through all of the necessary adaptations to become non-sucky, taking advantage of the neuroplasticity of the brain and nervous system to lock in a skill. But perfection is an illusion, there will always be something remaining that we will want to suck less at.

“That's what playing music is. It's not the mastery of any one instrument, it's the mastery of the art of sucking at something” - Chris Hayzel

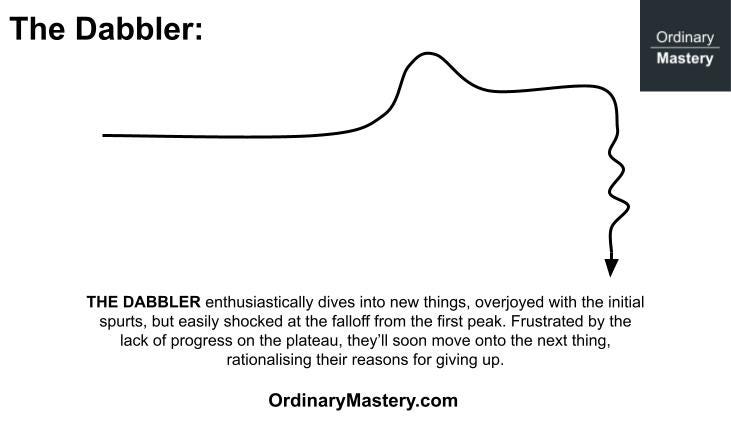

Chris points to the ever-present social media images of people living their best lives and how easily people get discouraged when trying to pick up new skills. This reminds me of The Dabbler archetype described by George Leonard in his 1992 book ‘Mastery’.

Leonard talks of contemporary society having an anti-mastery culture of cheap thrills and easy rewards where we seek climax after climax without being willing to endure the hard slog of practising on the plateau to achieve something worthwhile.

Thankfully, we are not all swayed by societal drives for quick fixes, immediate gratification, and surface-level hacks, and there are many contemporary artists who defy the ‘prodigious conspiracy against mastery’, as Leonard puts it.

Returning to Chris’ video, he points out that everyone you look up to, every artist you see looking good at one particular thing, is painfully familiar with the frustrations of feeling like they suck. But we never see them when they’re struggling alone with their practice, we never see their slow process of trying to get better. Chris asserts that if we could see more of what that process looks like, then perhaps more people would be inspired to embrace being bad at something and engage with their passions.

Comfort with sucking requires the beginner’s mind - the beginner has nothing to lose, and failure has no cost. A toddler gets straight back up after stumbling, happy that they are stumbling in the right direction. Non-beginners are handicapped by their sense of status, pride and self-esteem, and may have to re-discover the beginner’s mind to tolerate and embrace sucking.

Every note Chris plays during a performance has been meticulously planned and rehearsed, leaving nothing to chance in order to hide his suckiness. He is inviting his subscribers to join him on a journey of learning how to suck at something in order to get better at it. This is the essence of a path of mastery, deliberately seeking feedback to find all the ways that we suck, and doing the necessary practice to suck less.

“I'm hoping that by allowing you all to watch me be bad at something it'll encourage you to allow yourself to be bad at something too.”

“Understand that music is all process, it's all journey, no destination, because no matter how good you get at something there's always going to be something about it that you suck at. We are always the student. There's no such thing as mastery.” - Chris Hayzel

In my thinking about mastery, I’m seeing the term ‘mastery’ from two perspectives:

Firstly it denotes expertise in a particular domain, but at what level is mastery achieved? I’d say it is rather amorphous, there is no definable threshold, and those people we might consider masters are unlikely to see themselves in that way. Mastery is a never-ending journey beyond mere expertise. The beginner’s mind is the mind of mastery.

Secondly, and more importantly, I see mastery as an attitude. I’ve called my Substack ‘Ordinary Mastery’ because I see mastery primarily as an attitude which is available to all of us, in any walk of life. Whether someone wants to finally gain mastery over their eating habits and health, or whether they are pursuing mastery of the violin, the same key principles apply: Commitment and a dedicated practice that is aligned with our internal values.

Mastery entails being comfortable with being uncomfortable. Avoiding the temptation to practice the things we already know well and to tolerate feeling like a fool, like a beginner, tackling the things we don’t yet know which will pull us towards a future stage of development. And I’m not lecturing you here, I’m talking to myself, because my guilty secret is that when I’m practising on the piano, guitar, or drums, my sessions so often veer towards things I already know, things that sound pleasing to my ear.

When there is no one around to hear my mistakes - my total suckiness - I’m often guilty of pretending they didn’t happen. Denial feels good. Even though I know that we should be at peace with our suckiness and treat mistakes simply as data, and to help us to know what to work on.

I must continually remind myself of the three F’s of skills practice:

Focus

Feedback

Fix-it

The three F’s are explained by Eric Anders and Robert Pool in their book ‘Peak’ which is an analysis of the science of expert performance. We need to focus on our execution, attentively embrace mistakes as feedback, and analyse why the mistake occurred so we can fix it. This kind of practice requires concentration, and it can be exhausting, but it is the kind of deliberate practice that yields results. Denial of our mistakes simply stunts our growth.

Mistakes as the portals of discovery and triggering neuroplasticity

“Mistakes are the portals of discovery” - James Joyce

In his podcast episode, How to Learn Skills Faster, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman explains that we can leverage errors to accelerate our skill learning and how errors solve the very problem of knowing what to focus on while learning.

Huberman asserts that even if we are getting something wrong 90% of the time, we should continue practising, and continue maximising the repetitions because the errors actually cue our nervous system in two ways:

Firstly, errors cue our nervous system towards error correction;

Secondly, they ‘open the window’ for brain neuroplasticity.

Huberman refers to a paper from the journal, ‘Neuron’, entitled ‘Post Error Recruitment of Frontal Sensory Cortical Projections Promotes Attention’. This paper suggests that the areas of the brain which anchor our attention are immediately activated after making an error.

The errors tell our nervous system that something needs to change and ensure our attention is directed to the errors. This opens the possibility for plasticity, the means by which the brain adapts by making the appropriate neural connections through the release of neuromodulators such as dopamine, acetylcholine, and epinephrine. If we put down the guitar or golf clubs in self-disgust at our suckiness, we are preventing the brain from adapting in the ways we want in order to improve. Instead of denying our suckiness, we actually want to pay attention to it, so we can harness the brain’s adaptability. The more we push ourselves to suck and make mistakes, the more plastic the brain will become, so when we finally get things right the correct pattern will be rewarded with the release of dopamine and consolidated as neural connections in our brain.

Huberman’s analysis contradicts some of my previous assumptions about practising, particularly from what I’ve picked up in advice about learning the guitar. I’ve always worked with the understanding that if you are making mistakes, you need to slow down the tempo, until you can play the piece flawlessly, and then gradually speed up to lock it in. I had thought that by repeatedly playing the error, you would be learning to play it wrongly. But it seems that playing at tempo and making mistakes might not be such a bad approach after all.

This aligns with the findings of Anders Ericson which related to getting out of your comfort zone.

“Push yourself well outside of your comfort zone and see what breaks down first. Then design a practice technique aimed at improving that particular weakness.” - Peak by Anders Eircson and Robert Pool

Similarly, in his book, Mastery, while George Leonard stresses the importance of having patience on the plateau, being “zealots of practice” and “connoisseurs of the small iterative step”, he also cites the paradox of those we consider as ‘masters’ who mix up their patient practice with occasionally “exploring the edges of the envelope”, going precariously outside of one’s comfort zone to test our outer reaches of capability.

While researching the topic of failure opening the door to neuroplasticity I found a piece on the JustinGuitar channel which also references Huberman’s work. In addition to the ideas around using failure to trigger neuroplasticity, Justin references another Hubaman podcast, Using Failures, Movement & Balance to Learn Faster, which has prompted him to do 5 minutes of handstand attempts prior to practising. Why? Because the conditions for neuroplasticity arise as a result of physical exercises involving balance where you are likely to be wobbly and frustrated - and those neurochemicals for plasticity remain in your brain for a while after the exercise.

“Disrupting your vestibular motor relationship… can deploy or release neurochemicals in the brain that place you into a state that makes you much better at learning and makes making errors much more pleasureful.” - Andrew Huberman

Huberman advises us to explore the “sensory-motor vestibular space” through novel body positions involving gravity - yoga, gymnastics, handstands or non-stationary road bikes. Personally, I’ve often spoken with friends about the virtues of flatwater marathon kayaking, where you are constantly challenged to balance in a skinny, but fast kayak. Now it makes more sense, it is creating the conditions in my brain for neuroplasticity.

Perhaps that’s a good argument for incorporating unicycling, skateboarding, and slack-lining into the office environment!

Mastery is never accepting that you've reached your peak, there is always more to work on. Linger too long on how much you suck and your progress will languish, and sucking soon becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The urge to create, the calling to be the best you can be, can outweigh the immediate needs for status, validation, and approval that make us feel sucky when we don’t get them.

The paradox of sucking is that if we want to suck less, we have to tolerate sucking more. If we never get out of our comfort zone and embrace the suck, then our suckiness will persist. The lasting lesson is worth more than the momentary pain of the mistake. Errors are the table stakes for growth.

Chris Hayzel’s video on mastering the art of sucking really resonated with me and trawling through some of his other videos I stumbled across a most remarkable ‘error-free‘ rendition of Prince’s When Doves Cry - an incredible solo effort using a looper. Be sure to check it out. To my ears, this is as close to perfection as it gets, the artistic thought, structuring, and performance planning that goes into something like this requires quite a commitment. But I’d be willing to bet that there are tiny nuances that only Chris notices, which he still feels he could improve upon. Mastery is a journey without a destination.

"Mastery is never accepting that you've reached your peak, there is always more to work on."

This is an impactful sentence John. We too often think of learning a skill as getting from A - B or going from 0 - 1 when in reality that is not the case. I think embracing that early on and enjoying the process of learning is so important.